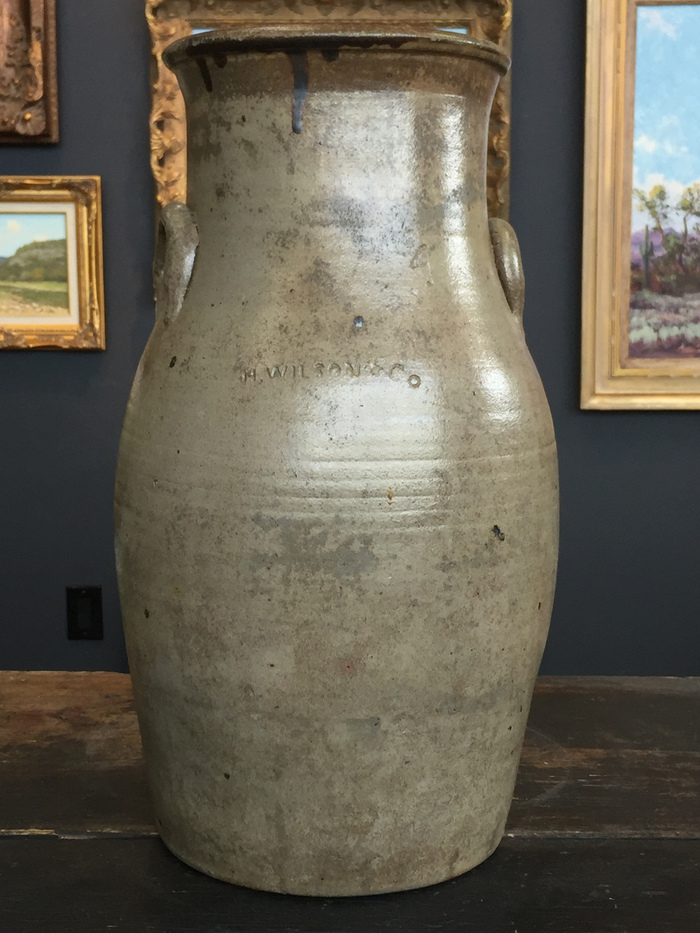

H. Wilson Circa 1860s

Paintings

- H. Wilson

- Circa 1860s

- Seguin Texas Potter

- Size: 4 Gallon Churn

- Medium: Pottery

- Circa 1860s

- 4 Gallon Churn Ultra Rare

- View details

- Contact for Price & Info

Biography

H. WilsonCirca 1860s Seguin Texas Potter

Biography

Wilson Texas Pottery Stoneware

(1857-1903)

History

The History of Wilson Pottery and the Endeavors of the Post Slavery Potters

In the second half of the 19th Century, from 1857 to 1903, Wilson Pottery was manufactured in the Capote Hills, which is located approximately 10 miles East of Seguin in Guadalupe County. At that time, there were three Potteries involving Wilsons as Potters. The first was identified archeologically as 41-GU-6, John McKamie Wilson's Guadalupe Pottery; the second, 41-GU-5, H. Wilson & Co.; and the third, 41-GU-4, Durham-Chandler-Wilson.

The pottery business in the area began in 1857 when Reverend John McKamie Wilson, Jr., a Presbyterian Minister, moved into the area bringing with him his family and 20 slaves. He hailed from Burke County, North Carolina, spending some time in Fulton, Missouri and then moving to Texas in 1856 to maintain his slaves, undeterred by the laws against slave ownership.

Finding the type of clay needed to produce quality utilitarian pottery drove his decision to settle his slaves in Capote to form the pottery business. Not being a potter himself, he hired professional potters to teach his slaves the pottery craft. Thus the Wilsons, while still in bondage, learned the craft, and became quite skilled at it, and the business prospered. Having been successful potters while in bondage, it was the logical next step to form a similar business, once they were free. This is exactly what they did.

The Wilson Pottery

All of the Wilson Pottery is rare, of high quality, and highly collectible. It is pottery that the public shows great interest in. Numerous pottery exhibitions have been held in Fine Arts Museums and some even have permanent collections. For example, there are currently exhibitions at The Witte and Institute of Texan Cultures in San Antonio and The Bob Bullock Texas History Museum in Austin. The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston sponsored an exhibition about the Wilson Potters and their pottery. The Curator, Michael Brown, gave a lecture as well as wrote a very well received book about the potters entitled, MFAH The Wilson Potters, An African-American Enterprise in 19th-Century Texas. The book published in conjunction with the exhibition in November 3, 2002 - March 3, 2003 and has the same name as the exhibition.

We are in need of benefactors to help fund the purchase of the pottery for the Wilson Pottery Museum. There are collectors willing to sell, but at a price out of range for most to attain. According to reports, the Wilson Pottery business was prolific and flourished throughout the south and southwest, reaching as far as California. Statistical information recorded accounts for as many as 1,000 pieces remaining as collectors items. Not only is the pottery produced by these post slavery potters greatly appreciated, but the potters have also been recognized as the first African-American Entrepreneurs in Texas. The Public Schools of Texas also include them in their seventh grade History Text.

Hiram Wilson's endeavors were varied, but his life was cut short. However, James and Wallace remained potters until the third-site Durham-Chandler-Wilson pottery business terminated in 1903. Nearly a hundred years later, our family applied for and received a grant from the Texas Historical Commission to acquire this historic site property for preservation purposes. The property with survey designation, 41-Gu-4, is located on approximately five acres, with the pottery kiln locations enclosed with fencing to help preserve their historic value. Future plans are to erect a living museum that depicts as much as possible operations at the site when it was active. Plans for the surrounding area include building an Information Center, a park with a picnic area, and a beautiful garden with indigenous plants.

In 2012, we were blessed when the City of Seguin granted the Wilson Pottery Foundation use of the historic Sebastopol House as home for the Wilson Pottery Museum. The museum opened in June 2013.In 1856, the Reverend John McKamie Wilson Jr., a Presbyterian minister and entrepreneur interested in clay science, relocated from North Carolina to Texas. There in the Capote Hills—a rural, sparse enclave in Guadalupe County, 12 miles from the town of Seguin—Wilson opened a business called Guadalupe Pottery. Wilson mainly sold jugs, churns, crocks and cemetery flower jars. The pots featured crescent handles and a deep chocolate-colored interior of liquefied clay. Before refrigerators and iceboxes, high-fire, nonporous pottery was essential to life—the Tupperware or Ziploc bags of the 19th century. Clay pots preserved everything from grains, beef and butter to whiskey and even drinking water. The potters who worked under Wilson’s direction mostly used alkaline glaze, one of the oldest methods in ceramics, to create a glassy exterior from a slurry of wood ash, sand and clay. An arduous process in the 1850s, it took days to stoke underground wood-burning kilns to a high enough temperature for a successful firing.

Three of Wilson’s potters were enslaved servants who traveled to Texas with him—Hiram, James and Wallace. For more than a decade, these men were responsible for nearly every facet of Guadalupe Pottery’s production: from mixing clay and expertly “throwing” the pots on a kick wheel to glazing and stacking vessels and meticulously controlling the temperature and duration of the kiln’s flames. The men kept working for the reverend even after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. In Texas, slavery didn’t end until June 19, 1865, when Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston and issued General Order No. 3, informing the people of Texas that all who’d been enslaved were free—the event commemorated as Juneteenth.

Paula King Harper, a descendant of Hiram Wilson, sits on the steps of the Sebastopol House in Seguin, Texas, with Wilson vessels from her own collection. Harper leads the Wilson Pottery Foundation and coordinates the Wilson Pottery Show each October. DeSean McClinton-HollandIn 1869, Hiram founded his own stoneware business at a new site with James and Wallace, H. Wilson & Company. (Though not biologically related, all three took their enslaver’s surname, the practice of some Black Americans at the time.) Some scholars believe that H. Wilson & Company was the first business in Texas founded and owned by formerly enslaved people.

Pots created by the hands of Hiram Wilson and his colleagues have been passed down through households and sold at garage sales over the course of many generations. Today, their rich history, as well as their distinctive styles and glazes, make the jugs sought-after acquisitions for museum collections. Left to right: A preserve jar, a three-gallon butter churn and a large jar with a lid from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; a stoneware jar from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (3); NMAHA century and a half later, the pots they made are celebrated in the ceramics world. In silvery grays and greens, with uneven salt drips and textured glazes that resemble the moon’s surface or, sometimes, an orange peel, Wilson wares are coveted both as objets d’art and for their extraordinary story of Black self-determination in the postwar South. Wilson pottery now resides in museums across the United States, from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston—an indelible part of the country’s entrepreneurial and creative heritage.

Related video: History unearthed in Williamsburg (WFXR Roanoke)

finds that date back to the days before the foundingCurrent Time 0:04/Duration 2:06

WFXR Roanoke

History unearthed in Williamsburg0

View on Watch

The story of Hiram, James and Wallace Wilson is woven through with threads of folklore, given the sparse records kept at that time, particularly for people born into slavery. But over the last 50 years, researchers have uncovered more details about the Wilsons. Georgeanna Greer—a San Antonio pediatrician and ceramics collector-aficionado—was passionate about locating abandoned kilns, and she left a trove of Wilson information behind, including a 1973 taped interview with James Wilson’s son, James Wilson Jr.

Capote Baptist Church has been in the midst of a restoration since 2012. After a new pastor, Terry Williams, arrived, its membership surged from 4 congregants to 85. DeSean McClinton-Holland

A wooden cross on the property of the Capote Baptist Church that Hiram Wilson founded in 1872 DeSean McClinton-HollandEmancipation offered the Wilsons an opportunity none had ever expected. Establishing a pottery business was complex and costly. It meant finding a suitable site, testing clay, constructing a kiln and hiring proficient workers. And the men did all this in an “intensely dangerous environment,” said Ashley Williams, a recent fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. In the late 1860s, Black residents of Guadalupe County “filed almost 200 complaints with the Freedmen’s Bureau for unpaid wages and violent crimes” perpetrated against them. A Baptist missionary from Maine, the Reverend Leonard Ilsley, helped Hiram buy 600 acres of land for $500 and likely either gave Hiram a personal loan or served as a guarantor in the transaction. When Hiram died in 1884—survived by his wife, Senia, and 11 children—Ilsley served as administrator of his estate.

One of Hiram’s great-great-granddaughters, LaVerne Lewis Britt, first discovered her connection to the potters after her retirement, when she became interested in genealogy. Over the course of five years, she researched and wrote a book called , which describes how her ancestor created a thriving post-slavery community in Capote. Hiram set aside 10 of his 600 acres for a Baptist church and became its minister. The white steepled chapel remains active today, beside a cemetery with cedar and crape myrtle trees. Many Wilsons have been laid to rest there, including Hiram, whose grave is marked by a tall obelisk.

Pastor Terry Williams has been leading the Capote Baptist Church since 2015. When he arrived, he says, he felt the spirit of Hiram Wilson and other former slaves who founded the church in 1872—“a cold breeze coming up in the summertime.” DeSean McClinton-Holland

A Bible rests on the piano at Capote Baptist Church. Right, the building has been in the midst of a restoration since 2012. After Pastor Williams arrived, its membership surged from 4 congregants to 85.Hiram also founded a one-room schoolhouse where Paula King Harper, another of his descendants, says her grandmother once taught. King Harper is the current president of the Wilson Pottery Foundation. On the phone, she described how interest in her celebrated ancestor’s technique has spread in collector circles since the organization’s founding in 1999. A pottery collector in San Antonio was at a garage sale and noticed the green salt glaze drip from underneath dirt that had dried on a gallon jug. “They purchased it for less than $10, went home, cleaned it up, and guess what it was? A stamped H. Wilson.” Finding that stamp is now the equivalent of finding a signed painting by a renowned artist. King Harper once sat at an auction that included several pieces of Wilson pottery from someone’s private estate. “There was a beautiful, pristine five-gallon jug I watched sell for $12,000,” she said.

Traditionally, clay artists, who made quotidian jugs and jars rather than purely aesthetic works, have been considered second-tier makers, ranking below sculptors. But over the last few decades, contemporary and historic ceramicists like the Wilsons are receiving new scholarly and art-world attention. Williams, the recent Smithsonian fellow, is researching the Wilsons as part of her doctorate at Columbia University. She notes that most enslaved potters wouldn’t have been able to inscribe their names or initials on a pot. But once the Wilson potters were free, they added a maker’s mark, which made all the difference. Future generations were able to dive into the records and find out more about the remarkable potters. “Because we can tie the makers to these objects, which is so rare, it allows us to see the story about the resilience of the Wilson potters during slavery, and their extreme success and survival,” Williams said.

Elmer Joe Brackner Jr. was a graduate student in anthropology at the University of Texas when he unearthed buried ceramic shards and located the original kilns at two different H. Wilson & Company sites. DeSean McClinton-Holland

Ashley Williams, a recent pre-doctoral fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, has been researching the Wilson potters as part of her PhD dissertation on crafts made by enslaved and imprisoned artists. DeSean McClinton-HollandThe Wilsons’ style may have been influenced by the works coming out of the Edgefield district in South Carolina, a place then known as a kind of pottery Mecca. It was famous for massive, bulbous jars and glazes, features that the early Wilson pots share. Edgefield has its own significant history of highly skilled Black craftsmen, including David Drake, the earliest known enslaved potter to inscribe his work.

Collectors look for these distinctive elements when they’re hunting for Wilson pottery pieces: the official maker’s mark stamped by H. Wilson & Co.; a drip of salt glaze, an effective waterproofing agent that also gave Wilson pots their bumpy texture; a sturdy horseshoe-shaped handle. DeSean McClinton-HollandLater, the Wilsons’ pottery took on more distinctive features. The men started out using alkaline glaze, but once they opened their own business they switched to salt glaze, likely for its strength and waterproofing properties. Salt glaze also produces more consistent colors and textures, such as the bumpy orange-peel finish admired by H. Wilson & Company collectors. At the time, the method was uncommon in Texas, according to Michelle Johnson, project manager of the William J. Hill Texas Artisans and Artists Archive at the Bayou Bend Collection and Gardens, part of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. “And it was dangerous,” she said, because salt glaze produces highly toxic chlorine gas from the wet salt thrown into the kiln during firing. (For this reason, contemporary ceramicists avoid the method altogether.) The Wilsons may have learned the technique from Isaac Suttles, an Ohio-born potter known for salt glazing, who is listed in the United States census as living in Seguin at the time.

The Sebastopol House, a Greek Revival home, was built in the 1850s by enslaved laborers who had advanced skills in working with concrete. Today, the building houses the Wilson Pottery Museum. DeSean McClinton-HollandLid rims are another notable element of H. Wilson & Company’s jars. At the first pottery-making site, during their enslavement, the men made more tie-down rims—jars without lids that require paper or cloth as a cover, which were easier and faster to make. Later, at their own shop, they crafted rims fitted for lids. Those lid rims allowed for more watertightstorage, but they also required more sophisticated expertise.

If you think you may have stumbled on one of these treasures at a garage or estate sale, look for a horseshoe-like handle—the most significant visual identifier of a Wilson pot. It’s still unclear why Hiram, James and Wallace switched to these thicker, rolled handles from their original Edgefield-inspired crescents. It may have been because horseshoe handles are sturdier, offering more surface connection to the pot’s body. It’s another puzzling question that Williams is pursuing and hopes to answer in the future.

It took a long time for the art world to discover the Wilsons’ creations. After Hiram’s death in 1884, James and Wallace Wilson went on to work at another pottery site run by Marion Durham, a potter from South Carolina who had moved to Texas with John Chandler, who was most likely his enslaved servant at the time. By the time the Wilsons joined them, Durham and Chandler were in business together. That site closed in 1903. These pots remained in circulation, but many details of their story were lost.

Modern replicas of the Wilson pottery logo created by Earline Green. DeSean McClinton-Holland

Earline Green, an educator and a member of the Wilson Pottery Foundation’s board of directors. Green helps promote the potters’ legacy by demonstrating their innovative 19th-century techniques. DeSean McClinton-HollandDecades later, an anthropology graduate student named Elmer Joe Brackner Jr. conducted a magnetometry survey to find buried pottery. (Clay contains iron oxides that can become magnetized.) At the original Guadalupe Pottery site he found what’s known as a “groundhog kiln,” a uniquely Southern, semi-subterranean kiln used in the 19th century for firing alkaline-glazed pottery. At the second site, home of the independent H. Wilson & Company, Brackner found ceramic-glazed shards and another groundhog kiln. His research, and that of Georgeanna Greer, the ceramic historian, helped piece together the Wilsons’ unusual story.

After many years of advocacy by the Wilson Pottery Foundation, art historians and curators began scouring land deeds, court documents and handwritten capacity marks (numbers that denote the volume of each jug) to present a fuller picture of the Wilsons, sometimes correcting previous theories about their methodology and timeline.

Texas ceramic artist Earline Green researches the Wilsons’ past while creating her own pottery to honor their legacy. In 2018, she interviewed Wilson descendants and collectors and visited historical societies in Texas for archival information. Two years later, she curated an exhibition on her campus in Fort Worth; the show also displayed ceramic pieces she created based on the work of the Wilson potters.

Deacon Willie Hightower Sr., a descendant of Hiram Wilson and one of the current deacons at Capote Baptist Church. DeSean McClinton-Holland

Hiram Wilson’s grave in the cemetery outside the Capote Baptist Church. His 11 children had his tombstone inscribed with the words: “Our father has gone to a mansion of rest.” DeSean McClinton-HollandThe narrative continues to evolve, due in no small part to proud descendants of Hiram, James and Wallace. Every three years, hundreds of people gather in Seguin, Texas, for a jubilant three-day Wilson family reunion that is open to the public. In 2023, festivities included the Wilson Pottery Foundation gala and a tenth anniversary celebration at the Wilson Pottery Museum. The last reunion fell on the weekend before Juneteenth, and the reunion committee arranged a kickoff concert Sunday evening followed by Juneteenth events in Seguin’s downtown square.

“I was fortunate to grow up in Texas in the 1980s, around the time when our cousin LaVerne Lewis Britt had uncovered the history,” explains DeSean McClinton-Holland, the photographer of this story and a Wilson descendant through his maternal grandmother. “I grew up knowing bits of the story and visiting the church.” He describes the process of documenting Hiram Wilson’s legacy as a healing journey. “To think, he was born into slavery and was able to accomplish so much shortly thereafter,” he says. “It’s inspiring and motivating to think of all the freedoms we have now, and that we really have to push a bit harder.”