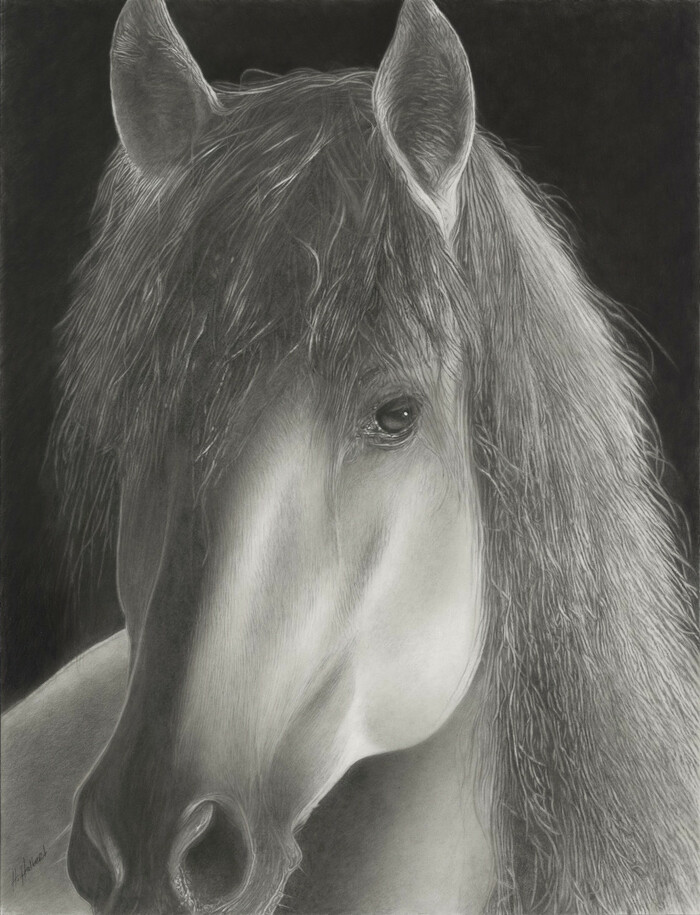

Howard Halbert "Andalusian" Spanish Horse

- Howard Halbert

- (Born 1957)

- Texas Artist

- Image Size: 29 x 22

- Medium: #2 Pencil on paper

- "Andalusian" Spanish Horse

- Contact for Price & Info

- View All By This Artist

Details

The Andalusian or Pura Raza Española, also known as the Pure Spanish Horse or PRE, is a Spanish breed of riding horse from the Iberian Peninsula, where its ancestors have lived for thousands of years. The Andalusian has been recognized as a distinct breed since the 15th century, and its conformation has changed very little over the centuries. Throughout its history, it has been known for its prowess as a war horse and was prized by the nobility. The breed was used as a tool of diplomacy by the Spanish government, and kings across Europe rode and owned Spanish horses. During the 19th century, warfare, disease, and crossbreeding reduced herd numbers dramatically, and despite some recovery in the late 19th century, the trend continued into the early 20th century. Exports of Andalusians from Spain were restricted until the 1960s, but the breed has since spread throughout the world, despite its low population. In 2010, more than 185,000 registered Andalusians existed worldwide.

Strongly built, and compact yet elegant, Andalusians have long, thick manes and tails. Their most common coat color is gray, although they can be found in many other colors. They are known for their intelligence, sensitivity, and docility. A substrain within the breed known as the Carthusian, is considered by breeders to be the purest strain of Andalusian, though no genetic evidence for this claim is known. The strain is still considered separate from the main breed and is preferred by breeders because buyers pay more for horses of Carthusian bloodlines. Several competing registries keep records of horses designated as Andalusian or PRE, but they differ on their definition of the Andalusian and PRE, the purity of various strains of the breed, and the legalities of stud book ownership. At least one lawsuit was in progress as of 2011 to determine the ownership of the Spanish PRE stud book.

The Andalusian is closely related to the Lusitano of Portugal, and has been used to develop many other breeds, especially in Europe and the Americas. Breeds with Andalusian ancestry include many of the warmbloods in Europe, as well as Western Hemisphere breeds such as the Azteca. Over its centuries of development, the Andalusian breed has been selected for athleticism and stamina. The horses were originally used for classical dressage, driving, bullfighting, and working livestock. Modern Andalusians are used for many equestrian activities, including dressage, show jumping, and driving. The breed is also used extensively in movies, especially historical pictures and fantasy epics.

Characteristics

Andalusian horses are elegant and strongly built with a straight or slightly convex profile. Ultra convex and concave profiles are discouraged in the breed and are penalized in breed shows. Necks are long and broad, running to well-defined withers and a massive chest. They have a short back and broad, strong hindquarters with a well-rounded croup. The breed tends to have clean legs, with no propensity for blemishes or injuries, and energetic gaits. The mane and tail are thick and long, but the legs do not have excess feathering. Andalusians tend to be docile, while remaining intelligent and sensitive. When treated with respect, they are quick to learn, responsive, and cooperative.

Two additional characteristics are unique to the Carthusian strain, believed to trace back to the strain's foundation stallion Esclavo. The first is warts under the tail, a trait that Esclavo passed to his offspring and which some breeders felt was necessary to prove that a horse was a member of the Esclavo bloodline. The second characteristic is the occasional presence of "horns", which are frontal bosses, possibly inherited from Asian ancestors. The physical descriptions of the bosses vary, ranging from calcium-like deposits at the temple to small, horn-like protuberances near or behind the ear, but these "horns" are not considered proof of Esclavo descent, unlike the tail warts.

In the past, most coat colors were found, including spotted patterns.Today, most Andalusians are gray or bay; in the US, around 80% of all Andalusians are gray. Of the remaining horses, around 15% are bay and 5% are black, dun, palomino, or chestnut. Other colors, such as buckskin, pearl, and cremello, are rare, but are recognized as allowed colors by registries for the breed.

In the early history of the breed, certain white markings whorls were considered to be indicators of character and good or bad luck. Horses with white socks on their feet were considered to have good or bad luck, depending on the leg or legs marked. A horse with no white markings at all was considered to be ill-tempered and vice-ridden, while certain facial markings were considered representative of honesty, loyalty, and endurance. Similarly, hair whorls in various places were considered to show good or bad luck, with the unluckiest being in places where the horse could not see them – for example the temples, cheek, shoulder, or heart. Two whorls near the root of the tail were considered a sign of courage and good luck.

The movement of Andalusian horses is extended, elevated, cadenced, and harmonious, with a balance of roundness and forward movement. Poor elevation, irregular tempo, and excessive winging (sideways movement of the legs from the knee down) are discouraged by breed registry standards. Andalusians are known for their agility and their ability to learn difficult moves quickly, such as advanced collection and turns on the haunches. A 2001 study compared the kinematic characteristics of Andalusian, Arabian, and Anglo-Arabian horses while moving at the trot. Andalusians were found to overtrack less (the degree to which the hind foot lands ahead of the front hoof print) but also exhibit greater flexing of both fore and hind joints, movement consistent with the more elevated way of going typically found in this breed. The authors of the study theorized that these characteristics of the breed's trot may contribute to their success as a riding and dressage horse.

Spanish horses also were spread widely as a tool of diplomacy by the government of Spain, which granted both horses and export rights to favored citizens and other royalty. As early as the 15th century, the Spanish horse was widely distributed throughout the Mediterranean, and was known in Northern European countries, despite being less common and more expensive there. As time went on, kings from across Europe, including every French monarch from Francis I to Louis XVI, had equestrian portraits created showing themselves riding Spanish-type horses. The kings of France, including Louis XIII and Louis XIV, especially preferred the Spanish horse; the head groom to Henri IV, Salomon de la Broue, said in 1600, "Comparing the best horses, I give the Spanish horse first place for its perfection, because it is the most beautiful, noble, graceful and courageous". War horses from Spain and Portugal began to be introduced to England in the 12th century, and importation continued through the 15th century. In the 16th century, Henry VIII received gifts of Spanish horses from Charles V, Ferdinand II of Aragon and the Duke of Savoy and others when he wed Katherine of Aragon. He also purchased additional war and riding horses through agents in Spain. By 1576, Spanish horses made up one third of British royal studs at Malmesbury and Tutbury. The Spanish horse peaked in popularity in Great Britain during the 17th century, when horses were freely imported from Spain and exchanged as gifts between royal families. With the introduction of the Thoroughbred, interest in the Spanish horse faded after the mid-18th century, although they remained popular through the early 19th century. The conquistadores of the 16th century rode Spanish horses, particularly animals from Andalusia, and the modern Andalusian descended from similar bloodstock. By 1500, Spanish horses were established in studs on Santo Domingo, and Spanish horses made their way into the ancestry of many breeds founded in North and South America. Many Spanish explorers from the 16th century on brought Spanish horses with them for use as warhorses and later as breeding stock. By 1642, the Spanish horse had spread to Moldavia, to the stables of Transylvanian Prince George Rakocze.

In 2006, a rearing Andalusian stallion, ridden by Spanish conquistador Don Juan de Onate, was recreated as the largest bronze equine in the world. Measuring 11 m (36 ft) high, the statue currently stands in El Paso, Texas.

Biography

Howard Halbert(Born 1957)

BiographyHoward Halbert was born and raised in North Central Texas, and early on developed an interest in portraying the horses, cattle and every day occurrences of the west, in pencil. Eventually Howard became a partner in a large ranching operation, which kept him away from his art for many years. A few years ago, Howard picked up a pencil and began to pursue his dream of becoming a professional artist. " I believe my passion and love of horses and the western way of life show in my work. I thank God for this gift which allows me to share with others what I truly enjoy. " Halbert credits Texas artist George Hallmark for recognizing his talent and encouraging him to pursue his calling. Halbert has participated in many Art and Museum Shows across the country including Cheyenne Frontier Days in Cheyenne Wyoming and The Small Works Great Wonders at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, OK. where his piece titled "Full Attention" won the prestigious Volunteer's Choice Award in 2016, his first year in the show. Howard currently resides in Cleburne, Texas where he is an active supporter of the Johnson County Children's Advocacy Center, which hosts the annual " Cowboys for Kids " benefit. Halbert's work can be found in numerous private collections.

BiographyHoward Halbert was born and raised in North Central Texas, and early on developed an interest in portraying the horses, cattle and every day occurrences of the west, in pencil. Eventually Howard became a partner in a large ranching operation, which kept him away from his art for many years. A few years ago, Howard picked up a pencil and began to pursue his dream of becoming a professional artist. " I believe my passion and love of horses and the western way of life show in my work. I thank God for this gift which allows me to share with others what I truly enjoy. " Halbert credits Texas artist George Hallmark for recognizing his talent and encouraging him to pursue his calling. Halbert has participated in many Art and Museum Shows across the country including Cheyenne Frontier Days in Cheyenne Wyoming and The Small Works Great Wonders at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, OK. where his piece titled "Full Attention" won the prestigious Volunteer's Choice Award in 2016, his first year in the show. Howard currently resides in Cleburne, Texas where he is an active supporter of the Johnson County Children's Advocacy Center, which hosts the annual " Cowboys for Kids " benefit. Halbert's work can be found in numerous private collections.