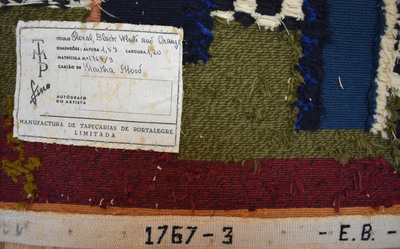

Martha Mood "Floral, Black, White and Orange"

- Martha Mood

- (1908-1972)

- San Antonio, TX artist

- Image Size: 59 x 46

- Medium: Tapestry

- "Floral, Black, White and Orange"

- Contact for Price & Info

- View All By This Artist

Details

Mid Century Modern

Biography

Martha Mood(1908-1972)

MARTHA MOOD

(1908–1972)

Martha Mood, artist, photographer, and teacher, was born in Oakland, California, on June 21, 1908, the second of three children of August and Martha (Glaser) Wagele, both of whom had immigrated to California from Germany. In 1915 the family moved to San Rafael, California, where Martha attended parochial school and Dominican College High School.

From 1926 to 1928 she studied art at the University of California at Berkeley, where she became familiar with Byzantine art and the work of Henri Matisse, both influential on her later work. She studied at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland in 1928–29 and subsequently returned to Berkeley, where she earned a bachelor's degree with honors in 1931.

She married John Homsy on the day of her graduation, May 16, 1931, and the couple moved to San Pedro, California, where they lived for nine years. During this period, Martha Homsy developed a toy business after she began making wooden toys for her two daughters. She also began experimenting with photography and provided photographs for a book by Dorothy Baruch, Parents and Children Go to School (1939).

In 1940 the Homsys moved to Honolulu, Hawaii, where Martha was involved in the production of five photography books on Hawaii. In 1945 the Homsys were divorced, and Martha returned to San Rafael with her daughters. After the war she married Beaumont Mood, a Texas photographer she had met in Hawaii, and settled with him in Dallas. She began ceramics lessons in 1946, but her artistic activities were curtailed by an auto accident in 1947. She suffered serious injuries to her face and jaw that required extensive plastic surgery.

In 1952 she and her husband moved to San Antonio, where she developed her métier as a stitchery artist. Initially she worked as an art teacher in public schools and at the San Antonio Art Institute. After a successful collaboration with architect O'Neil Ford, she established a business in which she produced lighting fixtures, fountains, pottery, and other architectural design objects with the help of her husband.

The Witte Museum mounted two solo exhibitions of Martha Mood's work during this period, featuring her photographs in 1953 and her ceramic sculptures in 1957.

Her involvement with appliqué stitchery was prompted by the fortuitous gift of fabric samples from a designer friend in 1959, at a time when Mood was reading a book on the creative possibilities of stitchery. Her earliest work was quite simple, merely glued arrangements of fabric shapes that nevertheless demonstrated her mastery of composition with color. She later began to experiment with embroidery, which gave an extra dimension of color and texture to the surface of her appliqués.

She used a mélange of "found" fabrics such as denim, velvet, silk, lace, old blankets, and used clothes in her wall hangings and amplified the textural richness of her embroidery by using yarns of different width, braid, and twine. Flowers, children, nudes, and wild and domestic animals were frequent themes in her wall hangings; she also made ecclesiastical banners and abstract works inspired by Matisse's cut-outs and the cubist collages of Picasso and Braque. Texas themes were reflected in works such as The Alamo (before 1968), Campfire (1963), Roundup (1965), Mexican Wedding (n.d.), and Hemisfair (1968). San Antonio's Mexican-American community was an important source of color and design in her work.

In her appliqué compositions, Mood used shallow space and expressively simplified form, both characteristic of modernism. She favored human subjects because "something beyond mere decoration is touched upon . . . deeper feelings and a sense of drama can be wonderfully achieved through the warmth and richness of the various fabrics." In Profile (1969), for example, she used lace, nylon hose, glittering mesh, and printed fabrics for an evocative portrait of a Mexican-American woman. She was masterly in using color to create a mood: in Gwendolyn (1968), a study of a young girl reading, she established a quiet, reflective atmosphere through the use of muted greens, blues, and lavenders, offset by the lightest accents of orange embroidery on the girl's lips and book.

Except in a few works, Mood stayed with fairly simple stitches such as the cross-stitch, running stitch, and daisy stitch. The vigor and simplicity of her work was influential on subsequent stitchery artists. Mood was one of the pioneers in elevating stitchery from craft to fine art. She traveled around the country to conduct workshops on stitchery and exhibited her work in more than thirty exhibitions in seventeen cities. As her reputation grew, she was commissioned to make appliqués for clients such as Mr. and Mrs. Lyndon Baines Johnson, Mr. and Mrs. John B. Connally, Mr. and Mrs. O'Neil Ford, and other prominent Texans.

In 1966 the Moods were divorced, and Martha Mood moved to Helotes, a suburb northwest of San Antonio. With the help of her daughter Susan Bragstad, she designed a home, Qué Lástima, and produced appliqué stitcheries with the help of a team of assistants. After 1967 she was represented by Lester Kierstead Henderson, a Monterey, California, art dealer who paid her a salary in exchange for receiving most of her work. In 1967 Mood's appliqué stitcheries were exhibited at the Witte Museum, and she received the San Antonio Art League's "Artist of the Year" award; she was the first worker in crafts to be so honored.

In 1968 she married Edgar Lehmann. She was diagnosed with cancer in late 1970, and died on July 15, 1972. With her permission, Henderson had many of her finest stitcheries reproduced in a more permanent and lucrative medium, large tapestries made by Guy Fino's Manufactura de Tapeçarias de Portalegre in Portugal.

Her reputation continued to grow after her death. The University of Texas medical school organized an exhibition of her work in 1972, and a memorial fund was established in her name by the Fiber Designers of Texas. In 1975, in response to public interest in Mood's work, Henderson organized an exhibition of thirty-eight Mood stitcheries and tapestries that traveled to a number of locations around the country, including the Rockford Arts and Science Center in Rockford, Illinois; the Charleston Art Gallery of Sunrise, Charleston, West Virginia; the Oklahoma Museum of Art, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum, Wausau, Wisconsin; and the Marion Koogler McNay Art Museum, San Antonio.

Her works are in the collections of the McNay Museum, the San Antonio Art League, Trinity University, and numerous private collections.

References

Lester Kierstead Henderson, The Sublime Heritage of Martha Mood (2 vols., Monterey, California: Kierstead Publications, 1980–83).

Martha Mood, "Make an Appliqué Tapestry," House Beautiful, October 1962.

Mary Carroll Nelson, "The Art of Stitchery: Martha Mood and Wilcke H. Smith," American Artist, October 1985.

Mary Carroll Nelson, "Martha Mood-The Sublime Heritage of Martha Mood, vol. 1," American Artist, October 1981.