H. Wilson & Co. (1869-1887)

Antiques

- H. Wilson & Co.

- (1869-1887)

- 1 gallon Signed

- Check out that big glob on the side of it.<br><br>Have hundreds of pieces of Vintage Texas Stoneware. Take a look.

- View Details

- Contact for Price & Info

- H. Wilson & Co.

- (1869-1887)

- 2 Gallon Jar

- 12.5 inches tall

- 9-inch diameter

- Texas Pottery / Stoneware Couple of hairlines and chips in the rim. Small hole on the bottom side.

- View Details

- Contact for Price & Info

- H. Wilson & Co.

- (1869-1887)

- 2 gallon Jar

- 14 inches tall

- <b></b>Utilitarian Stoneware

- View Details

- Contact for Price & Info

- H. Wilson & Co.

- (1869-1887)

- 2 gallon Churn

- Texas Antique Pottery, Stoneware. Utilitarian

- View Details

- Contact for Price & Info

- H. Wilson & Co.

- (1869-1887)

- 2 Gallon H. Wilson Jug Texas Pottery / Stoneware

- 15.5 inches tall

- 8.5 inch diameter

- Texas Pottery Stoneware

- View Details

- Contact for Price & Info

Biography

H. Wilson & Co. (1869-1887)

WILSON POTTERIES. The vessels made at the Wilson potteries of Guadalupe County

represent both the westward extension of Old South cotton culture and the

interaction of different cultural groups in mid-nineteenth-century Texas. During the

last half of the nineteenth century the three potteries in the community of Capote,

near Seguin, supplied a wide area of Central Texas with locally made stoneware

necessary for both food storage and preparation. In 1857 John McKamey Wilson, a

Presbyterian minister and educator, established the first Wilson pottery, which

produced utilitarian alkaline-glazed and salt-glazed stoneware through the Civil War

years. Rev. Wilson was not a potter, so the initial pottery operations were probably

conducted by his slave potters, Hiram, James, George, and Andrew Wilson. Between

1860 and 1866 a white potter, Marion J. Durham, from Edgefield, South Carolina, and

a black potter named John Chandler came to work at the site. Chandler might have

been a free man of color or may have belonged to Durham. Durham and Chandler

may have influenced the other potters, because most of the pottery found at the

earliest Wilson pottery resembles that of the celebrated Edgefield District of South

Carolina. The Edgefield District was a center of pottery-making in the South in the

early nineteenth century. Many scholars attribute the creation of the southern

alkaline-glazed pottery tradition to this period and place. This complex of

technologies included the use of an alkaline-based slip glaze, long-tunnel kilns

known as "groundhog kilns," and ovoid utilitarian forms sometimes decorated with

slip trailing. This southern pottery tradition spread westward with migrating potters,

both free and slave, who were largely trained in Edgefield. The pottery contrasted

sharply with the salt-glazed stoneware tradition that dominated the border South

states northward into the Ohio valley.The site of the first Wilson pottery near Seguin has most of the characteristics of

this southern pottery complex, including green, alkaline-glazed potsherds in a large

waste pile and the long, narrow surface indications of a groundhog kiln. However,

salt-glazed potsherds also littered the site. The presence of the salt glaze, which

was the preferred stoneware glaze from the Mid-Atlantic southern states and states

farther north, suggests the presence of a potter from that area. This potter could

have been one of the slaves or perhaps Isaac Suttles, an Ohioan who worked with

M. J. Durham and Thomas Chandler in 1870, and who could have been present at the

first pottery. The wide variety of vessel forms made at this first Wilson site attests to

the isolated frontier conditions in Central Texas. Forms such as chamber pots,

churns, bowls, pitchers and storage jars were made to satisfy local needs. The Civil

War disrupted the lives of all the potters in Capote. After the troops went home and

the slaves were freed, the potters at the Wilson potteries relocated to two separate

shops in 1869. One was run by M. J. Durham, with John Chandler and Isaac Suttles,

and the other was run by the former slaves, Hiram, James, and Andrew Wilson. H.

Wilson and Company was one of the rare examples of a pottery owned and operated

by a black man in the nineteenth-century South. Its product combined attributes that

can be traced to the earlier Wilson pottery, such as vessel shape and the use of a

groundhog kiln, along with some idiosyncratic additions, such as a new type of rim

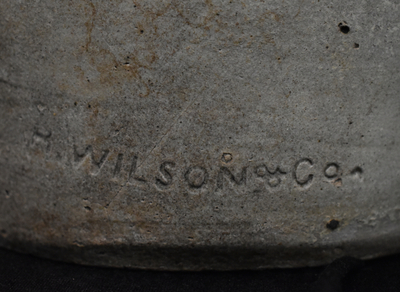

and handle. Hiram and Company only made salt-glazed ware and always marked the

vessels with the company's name, a practice not followed by most contemporaries.Hiram Wilson assumed a role in Capote similar to that of his former master in Seguin.

He started a church and a school, as well as a pottery. The separation of the black

Wilsons into a freedman's community may have been a response to postwar

violence and general hard feelings evident in reports of Freedman's Bureauqv

officers in Seguin. Two instances of violence against the Wilsons were reported in

1867. H. Wilson and Company went out of business about the time of Hiram's death in

1884. Some of the men, including James Wilson, then went to work with Durham and

Chandler at their pottery, which continued operation until about 1903.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:Joe Brackner, Jr., "The Transition from Slave Potter to Free Potter: The Wilson

Potteries of Guadalupe County, Texas," in Texana II: Cultural Heritage of the

Plantation South (Austin: Texas Historical Comission, 1982). Elmer Joe Brackner, Jr.,

The Wilson Potteries (M.A. thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1981).

John M. Wilson, Jr. became a key figure in the pottery trade in Texas after founding Guadalupe Pottery in 1857 in Guadalupe County, 12 miles east of Seguin. Wilson’s enslaved workers Hyrum, James, Wallace, George, and Andrew were instructed locally in the craft, where they honed their skills through practice and exposure to other potters.Following the end of the Civil War in 1865, Wilson’s newly emancipated laborers took his surname, a common practice at the time, and then formed their own company in 1869. H. Wilson & Company went into production between 1869 and 1872 on land granted to them by John Wilson, and is considered to be the first African American business in Texas. Years of experience working under Wilson provided the knowledge and skills needed to establish and operate a pottery. The enterprise’s success provided a livelihood for the potters that was different from the sharecropping and tenant farming that essentially tied African Americans to the land in a manner much like slavery.

The freedmen created a new style of pottery, breaking from the older traditions of their teachers. These new techniques included adding horseshoe shaped handles and signing their work. Prior to the Civil War, a potter working in the South rarely marked his wares, but by the 1870s the practice became more commonplace. The potters of H. Wilson & Company marked their wares with the company name, a promotional tool for identifying and advertising. More than that, the marks served as a symbol of their remarkable achievement within just a few years of emancipation. For Hyrum Wilson, the company provided a means to support his family and community, as well as serve as a spiritual leader. H. Wilson & Company became a symbol of what was now attainable in a new society.

Today, the archaeological evidence at the site of H. Wilson & Company provides an immeasurable amount of information about the company, as well as the community. These vessels can still be found today throughout central Texas in old barns and homes, as well as in antique shops, private collections, and museums. The Wilson Pottery Foundation, formed by descendants of the Wilson family, has opened the Wilson Pottery Museum in Seguin where the legacy of Wilson pottery is being preserved for generations to come.